“Ready-Made Ecologies": On the Production of Epistemic Ignorance by the Fashion Industry

- June 2023

★~(◡﹏◕✿) TO READ WITH

« Clothing should not only strive to be ecologically sustainable but also aesthetically and imaginarily sustainable. »

I often find myself questioning the environmental impact of fashion shows, particularly after having worked in production. I firmly believe that there is a delicate balance to be struck between conscious and sustainable fashion production, while still ensuring that fashion shows serve as significant highlights for fashion houses. However, I've noticed that as fashion shows become more extravagant, we seem to have limited access to genuine and precise information regarding their environmental impact. I wonder if the constant focus on the spectacular during fashion shows is just an efficient way to divert attention on the actual quality of the collections. At what point does it cease to set the tone for a collection and create a truly meaningful space to showcase it? This led me to feel increasingly conflicted about the progressive erosion of meaning and purpose in garments and clothing production. I feel a bit bored, and I don’t like it. It rekindles questions that I thought I had resolved back when I was ten years old: What distinguishes a designer from someone solely involved in the process of creating and selling clothes, regardless of their quality or price? Apart from the price tag and label, what sets elevated and luxury ready-to-wear apart from regular ready-to-wear? I firmly believe that we must continue to revisit these questions if we truly wish to think of fashion, clothing, and wearables. I’ve always regarded garments not only as items to wear, but as shapes and silhouettes that convey information and reshape our perception. They serve as a means for self-assessment, no matter how complex or simple they are. Watching the livestream of Louis Vuitton's "Spring 2024" or "Spring/Summer 2024" collection – we still don’t really know -, I felt extremely conflicted. First, because Pharrell’s appointment as the creative director of the French maison sparked numerous discussions about the required qualifications for such a position. Second, because I experienced a significant cognitive dissonance when I saw coats, shearlings, and fur walking a "SS" collection. Or is Pharrell actually trying to warn us about global warming????? Seasons don’t count anything anymore. But overall, like many others, I liked the collection, from the bags to the fits; it was an insightful proposition. The variety of looks and featured archetypes/core-aesthetics made it difficult to hate and it’s hard go wrong with almost 75 silhouettes, unless, of course, you're Maria Grazia. Anyways, the Vuitton boy, under Pharrell, could be anyone, the only thing is he drips ; as if he encompassed all of Pharrell’s fashion eras. Also, Pharrell was not alone; he was well-supported by the atelier.Despite my appreciation for the collection, I believe it relies heavily on aspirational products and aesthetics, lacking a sense of sustainability. It feels as though the intentional lack of overall coherence was designed to allow the marketing and sales team to set the tone for the next collection based on: which aesthetic that generates the most sales???? Let’s find out next season. This is just a hypothesis, but it raises some questions: Do we still rely on strict definitions to discuss fashion? Does the modern understanding and reception of fashion solely depend on aesthetics and visual pleasure? Lastly, are we truly considering sustainability in terms of collections, aspirations, and consumption?The fashion and luxury industry, as a whole, upholds its commitment to “ecology”, the “environment”, “savoir-faire”, and “durability”. Yet, it’s easier said than done. I do believe that the lack of philosophical and epistemological examination of fashion enables brands to be selective when it comes to ecological matters. Sustainability is way more than simply consuming or producing less and better. Differentiating a simple garment from a designer piece remains a crucial conceptual distinction apart from being a socio-economic determinant, and again, it rarely means that the only difference lies in the tag or the price. Factors such as ideation, imagination, references, creative process, material and fabric selection, savoir-faire, and production methods can help reshape our understanding of the industry. Clothing should not only strive to be ecologically sustainable but also aesthetically and imaginarily sustainable.

In his book "Sociologie de la Mode," Frédéric Monneyron proposes approaching fashion from an anthropological perspective and reintroduces the notion of fashion imaginaries. Traditionally, fashion has been studied from sociological and anthropological perspectives, as both clothing and the discipline itself serve as social markers and diacritic signs. It allows individuals to position themselves socially, "because the imaginaries it proposes also provide the possibility of delving beneath the social surface, into social depth, and uncovering the patterns, archetypes, and ultimately, the anthropological structures that define an era and create its meaning.". While I agree with this assertion, I also believe that fashion is often confined to the realms of the imaginary and the perceptual. Garments are more than just signs, social indicators or “inspo” and aesthetic referents; they also convey information as they mediate our relation to alterity. They convey a knowledge that goes beyond a pure sociologic standpoint, especially in their contemporary context. The philosophical and epistemological perspective are seldom considered. Thus, it’s necessary to reinsert the notion of “materiality” when thinking of clothing. That’s something that most designers do, and researchers rarely listen to. I’d argue that this is due to the metonymic functioning of the industry, where “fashion” implies the textile industry without explicitly naming it. Through this unnamed yet essential relation, we are being made oblivious of the environmental impact of the fashion industry. This “impact” encompasses our consumption habits, the fabrication and production process of textiles, the marketing and communication strategies implemented by different actors in the industry, and the progressive consumer awareness. Ultimately, it all comes back to garments being made of textiles, and textiles being made of fibers (natural/semi-synthetic/synthetic) and fibers being a material.

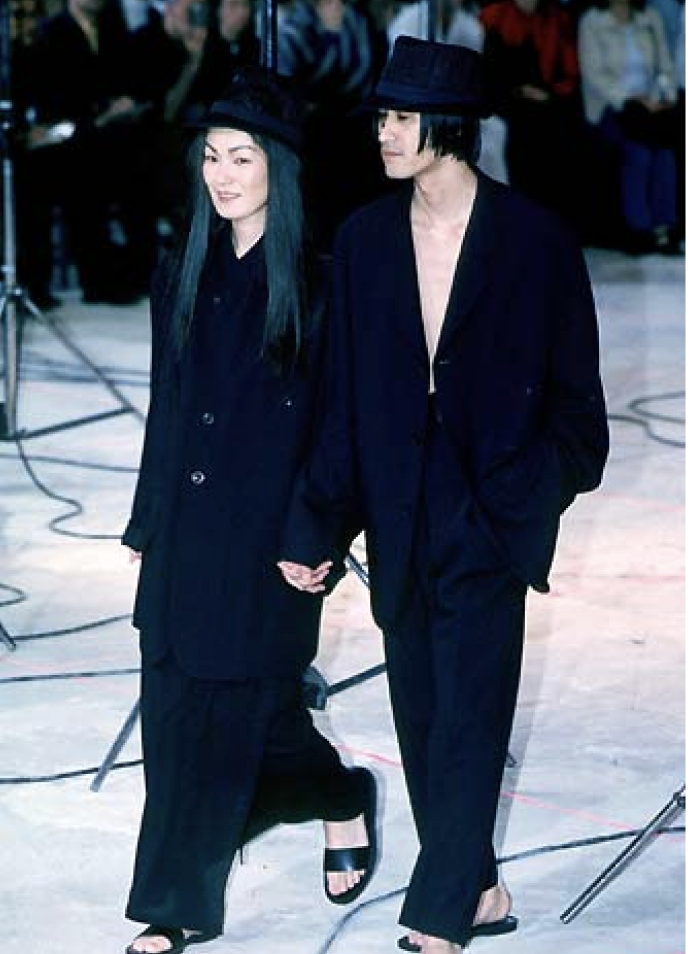

The leap from the textile industry to the fashion industry represents an epistemic shift that, in my view, makes it impossible to synthesize the disciplines and fields of action of the industry as perceived by consumers. We often forget what textile refers to, what’s a garment, and ultimately what fashion is and isn’t. Many would argue that this is about gatekeeping and social relegation, but I’d say that most of the clothing production nowadays has nothing to do with fashion the same as I would never call myself a painter because I simply can’t paint. The confusion and indefiniteness of terms within the industry as well as the lack of pedagogy allows it to position itself conveniently when it comes to sustainability and ecology. Some designers, like Yohji, would engage in a “war” against the dissolution of meaning within fashion, others like Marina Yee would keep on making collections only when necessary and not seasonally. Brands like Acne Studios would actually provide their consumers with well-detailed annual reports on their brand sustainability without opacifying the information. Yet, if everyone’s talking about sustainability, well they just be talking. Finally, our longing and love for clothing and hoarding help the dispersion of the notions of individual and collective responsibility, that “Am I the drama?” mindset finally gets an answer: YES. Because, after all, it’s just clothing innit? But behind that is a multiscale and multisectoral industry which is intrinsically opaque and produces ignorance to motivate consumption, just think about it.

One important epistemological leap dwells in the discursive practices of the industry. Marketing, although a disciplinary field, consists of a new form of speech and discourse aimed at promoting and enticing consumption. In the context of the climate crisis, we observe a shift in marketing and communication strategies aimed at alleviating guilt by shifting the focus of responsibility from the industry to consumers and promoting "eco-friendly" behaviors. Despite recognizing several innovations and ecological efforts within the fashion industry and the industry at large, three structural problems enable manufacturers, large corporations, and brands to maintain their production while minimizing their environmental impact through discourse.

Fashion, as it overshadows the textile industry, poses a first problem. It seems to directly benefit from its apparent incompatibility with science and research. It is still considered "superficial," "trivial," and "focused on appearance," especially among intellectuals, yet it capitalizes on its intellectual relegation. The disqualification of the discipline by the intellectual spheres prevents it from being understood in its entirety, which ultimately produces ignorance.

The commodification of garments also plays a significant part in the equation. Stripped from its original function and from the recognition of "design," clothing has become a commodity and a purely aesthetic reference. Consequently, clothing mediates our relationship with others from a socio-economic perspective and aesthetic standpoint. This shift is not only due to hyper-modernity and capitalism but also to the inherent opacity of textile production and manufacturing processes and the complexification of supply chains.

Lastly, I believe that the subversion of environmental issues into trends, such as "green fashion" and "eco-fashion," enables manufacturers and brands to widen the gap between the reality of the processes and the actuality of the environmental crisis. The appropriation of environmentalist terminologies and their selective dissemination through social networks, websites, and labels contributes to the distancing from the sense of urgency and the dispersion of responsibility. Once again, our "Dressed for the Apocalypse" TikToks are symptomatic of a fragile comprehension of the industry. This phenomenon is particularly visible in the ultra-fast-fashion and fast-fashion segments of the industry and is achieved through the creation of a so-called community between brands and consumers, utilizing a falsely agentive "we." This non-specific, diffuse, yet inclusive "we"/"us" is based on aspirational motivation to change and transform without feeling compelled to, giving a sense of acting ecologically while purchasing a product. The so-called community becomes an "interpretative community" convinced of their rightful and good actions. George Marshall addresses this matter in Don't Even Think About It… mentioning the usage of "we" in eco-friendly and falsely pro-climate communication strategies, stating, "I call it the 'slippery we' because it sounds inclusive and assertive when read in transcript but is actually ambiguous and often meaningless... the slippery we is a rhetorical gambit to create a sense of norm while demonstrating what management manuals like to call transformational leadership."

These three epistemic obstacles, which are beneficial to the industry, manifest in concrete practices and highlight the internal paradoxes of the industry. The industry has managed to create "ready-made ecologies" or "imaginary ecologies": the aesthetic and trend-based appropriation of manufactured objects devoid of their original function and design orientations. While this is less visible in the luxury industry, as it either doesn't address the issue or benefits from its status to guarantee the quality and durability of processes and garments, it becomes apparent when observing the coexistence of pseudo-sustainable lines with the approximately 17 annual collections produced by Zara or H&M. These are also supported by the implementation of "eco-friendly" programs such as the "Join Life Project" at Zara, while you still have to click on "See more" to access the properties of their products on their website ; or the intensive use of the falsely agentive "we" at H&M: "Let's innovate," "Let's Take Care," "Let's Change," but is that “us” in the room with us H&M???? I need to know. While the environmentalist terminologies abound and practices such as upcycling, recycling, reselling, and donating have become more widespread, facts remain unchanged. The textile industry still ranks 6th among the world's most polluting industries. It is the second-largest polluter of freshwater and is responsible for approximately 10% of greenhouse gas emissions. Also, it is important to distinguish among the various actors within the industry to clarify and contextualize our arguments. In general, the textile industry can be understood in terms of different textile producers and manufacturers, divided into producers of synthetic textiles and organic textiles. The fashion industry would be subdivided into different branches and subsectors (clothing, accessories, footwear, leather goods, etc.), with groups, conglomerates, brands, and fashion houses operating within them. These include fast fashion and ultra-fast fashion, mid-range ready-to-wear, and luxury/elevated ready-to-wear and haute couture.I think that it is crucial to emphasize the materiality of garments when considering them. The commodification of clothing, if historically situated, is unquestionable given that our clothes have become "aesthetic tokens" and "social indicators”. As Timothy Morton asserts in The Ecological Thought, any form of thinking that avoids acknowledging totality is part of the problem. However, while it may be challenging to think globally about everything in life, disregarding knowledge entirely is kinda problematic. We should at least fake it ‘till we make it. The influence of textiles and fabrics is to find within language and literature itself, as the word "text" echoes the act of weaving. Clothing, as the process of shaping and informing a textile through design, inherently encompasses knowledge and science. It is intertwined and interconnected, akin to a mesh. Whether organic or synthetic, textile refers to what can be woven or knitted, divided into threads or fibers – its original form – to create a piece of fabric, and it is an inherently circular process. For organic textiles, they rely on cultivation and chemistry for synthetic ones.Cotton itself, formerly the most produced fiber before polyester (in 2016, polyester production surpassed cotton with 48 million tons compared to 26 million tons for cotton), is worth interest. While the qualitative criteria to evaluate the durability and quality of a fiber are often ignored, the cultivation of cotton is conditioned by both climatic and human determinants with a consequent environmental and human impact. The massification of its production through techniques has led to the irrigation of 40% of cultivated areas, the use of pesticides, and the drying up of several rivers and seas, with the Aral Sea being the most famous case. Synthetic textiles like Viscose are often the product of large-scale production solution implementation. In 1884, when engineers Hilaire de Chardonnet and Auguste Delubac had the idea of reproducing silk in the laboratory after a silkworm epidemic impacted the French textile industry, Viscose, a plant-based artificial silk, was created. Viscose is often marketed as "biodegradable" while using several chemical and highly corrosive treatments. The traceability of the wood required to produce viscose is highly problematic, and since it is semi-synthetic and "biodegradable," it appears somewhat "natural." Polyester is, of course, even worse and responsible for the dispersion of microplastics in the air, oceans, and treated waters. And one thing to note is that we rarely check the tags before purchasing anything and that tags rarely precise the origin of the textile. My Proenza Schouler t-shirt for instance just tells me I’m wearing “100% cotton, Made in USA of Imported Fabrics”, but where from and made by whom? Globally, this is what is mostly shown in documentaries denouncing the textile industry and criticizing our consumption habits with shocking names such as "When Our Clothing Kills," with a great emphasis on the fast-fashion production processes. I have doubts about the effectiveness of these strategies; it is necessary to produce knowledge and content, yet pedagogy and knowledge transmission tend to work better. Perhaps it's because those documentaries are often too specific and avoid "totality," thus missing the balance between empathy and logic. The visual imagery of guilt is quite often mobilized and counterbalances the schematic nature of the production of knowledge in the industry. And if you want to shame people, I think that telling them their clothes look like shit works a bit better. The schemas explaining how a fabric is made not only obscure the reality of the process but also contribute to the invisibility of human intervention and labor. Attempts at ecological resolution and transparency through "labeling" inadvertently fit into this dialectic of schematization/invisibility by synthesizing discourse into signs and symbols. This paves the way for brands to create ecological imaginaries through so-called "sustainable" lines. The industry seems to be built on a network of invisible workers, even though it is "manufactured” and we refuse to think about it. It is most of the time relegated to systemic problems and a though a nihilistic "fuck the system" or "no future" vibe. I would say that the schematization of processes, coupled with the complexity of the supply chain, leads to epistemic opacity, defined by Paul Humphrey as the epistemic inaccessibility that results from the underlying properties and processes of certain computational systems, along with formal characteristics specific to the systems and social phenomena such as the division of labor and the limitation or inaccessibility that preconditions access to information, contributing to making a phenomenon epistemologically opaque. We must therefore recall that the rationalization and optimization of fiber production are achieved through the use of computational systems, same for the supply chain. The textile industry, by not implementing transparent communication strategies devoid of any educational purpose, produces epistemic opacity. It becomes impossible to think of clothing in its totality. At this point, dispersing responsibility the same way those spidermen point at each other in the meme. Finally, while we are increasingly driven by core aesthetics and archetypes instead of cultivating a fashion style and sense, we also project ourselves into perceptual categories. We have become somewhat predictable, and that's good news for brands. If the "end of fashion" and the rise of happy, trendy, hip, enthusiastic and sexy "I refuse to think" fashion reached its pinnacle with Ludovic de Saint-Sernin's appointment as Art Director of Ann Demeulemeester, we had a leap of faith and hope last May when he exited the fashion house. After only 7 months at Ann, he will be remembered for the amount of hate comments left under their publications. RIP, I guess. Maybe there's still a future for fashion, and maybe it can be sustainable, well-thought, informed, and designed. Is it responsible to seek for market approval and superstar designers if the collections don’t follow? What's significant in this and in the production of ignorance by the industry is that we tend to erase, once again, fashion history and legacy, to the formation of archetypal figures and aspirations. Fashion will always be aspirational, but it has yet to redefine these aspirations and ambitions. Archetypal fashion tends to obliterate the referential cultural environment in which collections are being produced. Micro-trends have annihilated that very principle by continuously proposing garments based on trends and core aesthetics. And while there are certainly common cultural references among individuals affiliated with a core aesthetic, it is more accurate to say that our relationship to those archetypes is based on the visual performance of oneself and the possibility of being identified and/or classified by peers on social media platforms. I’d say that the algorithmic structure of our exchanges and interactions, alongside with the segmentation of modes of representation/expression is responsible. It allows the industry and brands to offer clothing that corresponds to specific aesthetics and target their audience through data analysis and Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) in marketing. These quantification tools and evaluative systems not only maximize profit and guide brand strategies but also redefine the trend cycle to fit into niche markets. Overall, it's the industry's temporality and the value and durability of garments that are being redefined. This raises a question in terms of the ecology of creation and design. I’ll discuss resolution and innovative processes another time but from now on, think about it. xoxo, Go Piss Gurl- Cyana